Studio 7 Residency 2025 - Yasamin Khadembashi

Yasamin Khadembashi is an Iranian-Australian multidisciplinary artist with a BCA from Curtin University. Her practice focuses on painting, tattooing, ceramics, sculpture, textile, and installation. Influenced by her family’s experiences immigrating to Australia, she draws upon the cultural discourses surrounding post-9/11 Islamophobia, the 2005 Cronulla race riots, the Global War on Terrorism, and the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Her practice revolves around the identity crisis, confusion and displacement many queer Middle Eastern and Muslims feel growing up in the West. Yasamin’s work engages with issues experienced by first and second generation, people of colour and immigrants; often ostracised, marginalised and forced to assimilate. Her work explores the loss of

language, heritage, land, customs, beliefs, food, dance, music and ultimately identity when forced to integrate and navigate through unfamiliar and hostile environments.

Currently, Yasamin’s practice utilises the political and social discourses centred around the 2022 Women Life Freedom Revolution, magnifying women and queer rights violations within Iran. Her works reclaim identities cultivated out of shared experiences, isolation, and displacement, immortalising the lives of those living in the diaspora through the unorthodox materials and processes used in her practice.

Her work has been featured in numerous national exhibitions and competitions, including Home/Body at Artsource (2022), the Mosman Art Award (2022), Safe Space at ANUSA BIPOC (2022), the Redland Art Award (2022), and the Calleen Art Award (2022). In 2024, Yasamin undertook the Lake House Artist Residency at the Museum of Art and Culture (MAC)in Newcastle, as well as the Midland Junction Art Centre (MJAC) Residency. During her time at MJAC she was invited to judge the City of Swan’s annual Youth Art Exhibition, Hyperfest.

Whilst at PSAS Yasamin intends to produce a series of works that highlight the narratives hidden and erased from our contemporary society and our inherited history. The works produced will introduce and establish diverse identities and realities unfamiliar to the Australian western audience. During her residency Yasamin plans to develop a series of large and small-scale mixed-media sculptural self-portrait and portrait paintings, focusing on queer feminist theory, body-politics and anti-colonial discourses. The paintings function as visual commentary representing the struggle for bodily autonomy, safety, self-determination, educational and professional opportunities for women and queer people within Iran,

focusing on the current gender apartheid enforced by the regime in Iran and by the Taliban in Afghanistan.

RESIDENCY JOURNAL - January 2025

Transitioning into the Residency

To say these past two months have been a whirlwind is an understatement. At the start of the year, I was preparing to return to university and complete my Honours degree. Everything changed in an instant when I received an email from PS Art Space asking me to give them a call—they needed to discuss something with me. With my heart racing as I dialled their number, I had no idea what to expect. On the other end, they explained that the originally selected artist could no longer participate, and as their second choice, the opportunity was now being offered to me. I was completely caught off guard—shocked, speechless, and overwhelmed all at once. I had never expected to be chosen, let alone as an alternate, but here I was being given an opportunity I never saw coming.

It was one of those moments where time feels like it pauses, like the universe stops for just a breath to let the news settle into your bones. Then, a rush of adrenaline. Exhilaration. A sudden and overwhelming sense of gratitude. I rushed to Fremantle to see the studio for the first time, my mind already racing with plans—where my materials would go, how I would structure my workspace, how I could create a space where my art could take shape, unfettered and unapologetic. This opportunity would not have been possible without the encouragement of my Honours supervisor, Dr. Lydia Trethewey at Curtin University, who urged me to apply. I submitted my application on a whim, not knowing what to expect. My philosophy has always been: Apply, apply, apply! Apply to everything you can, because you have nothing to lose and everything to gain.

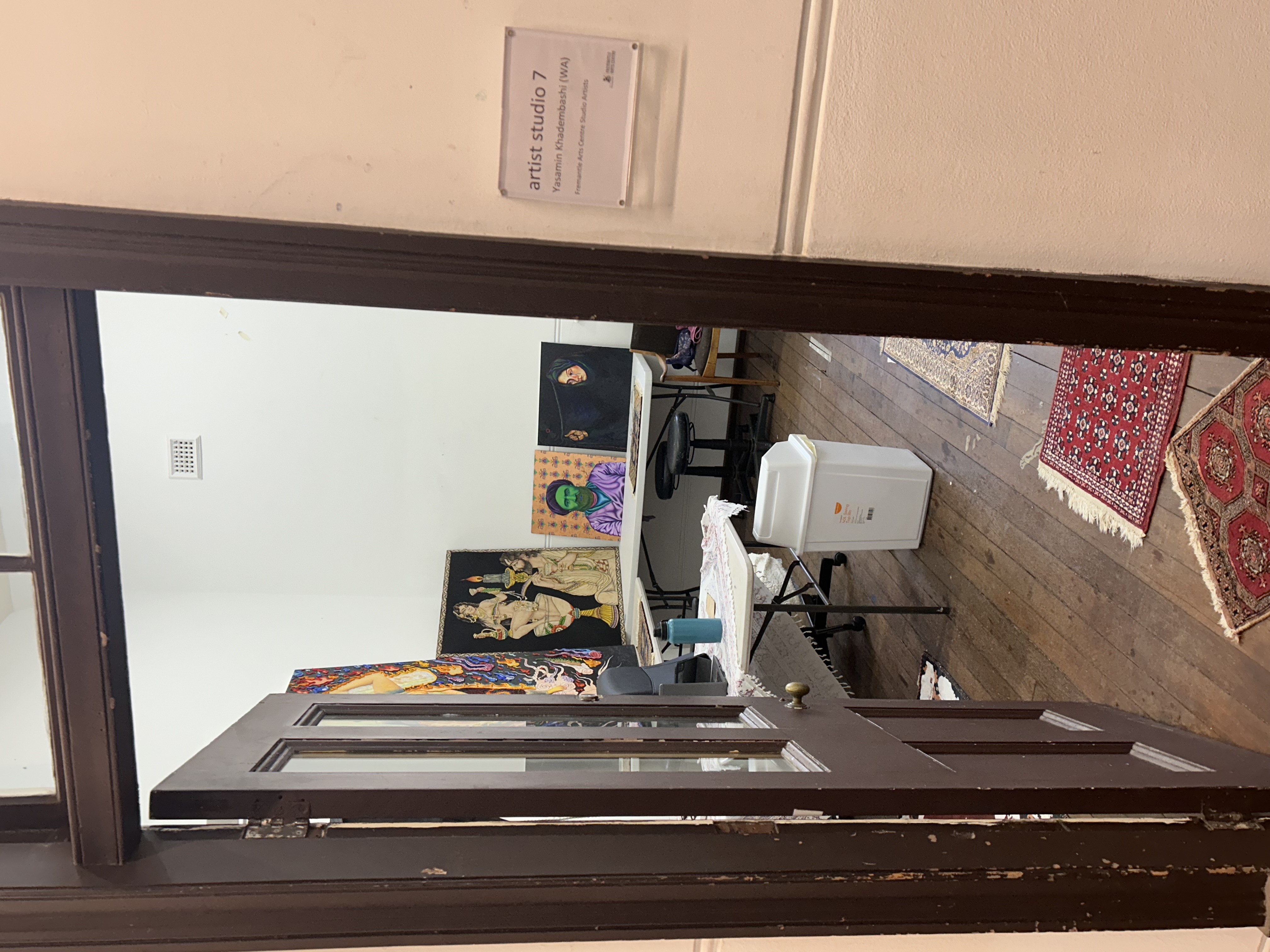

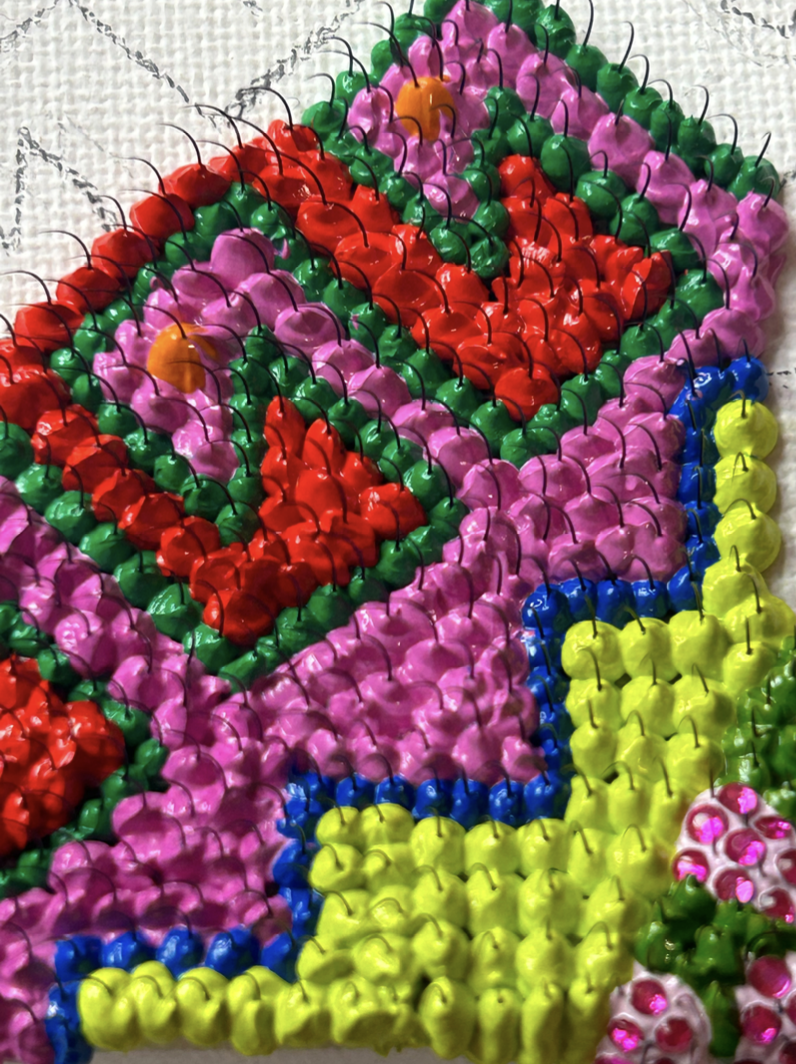

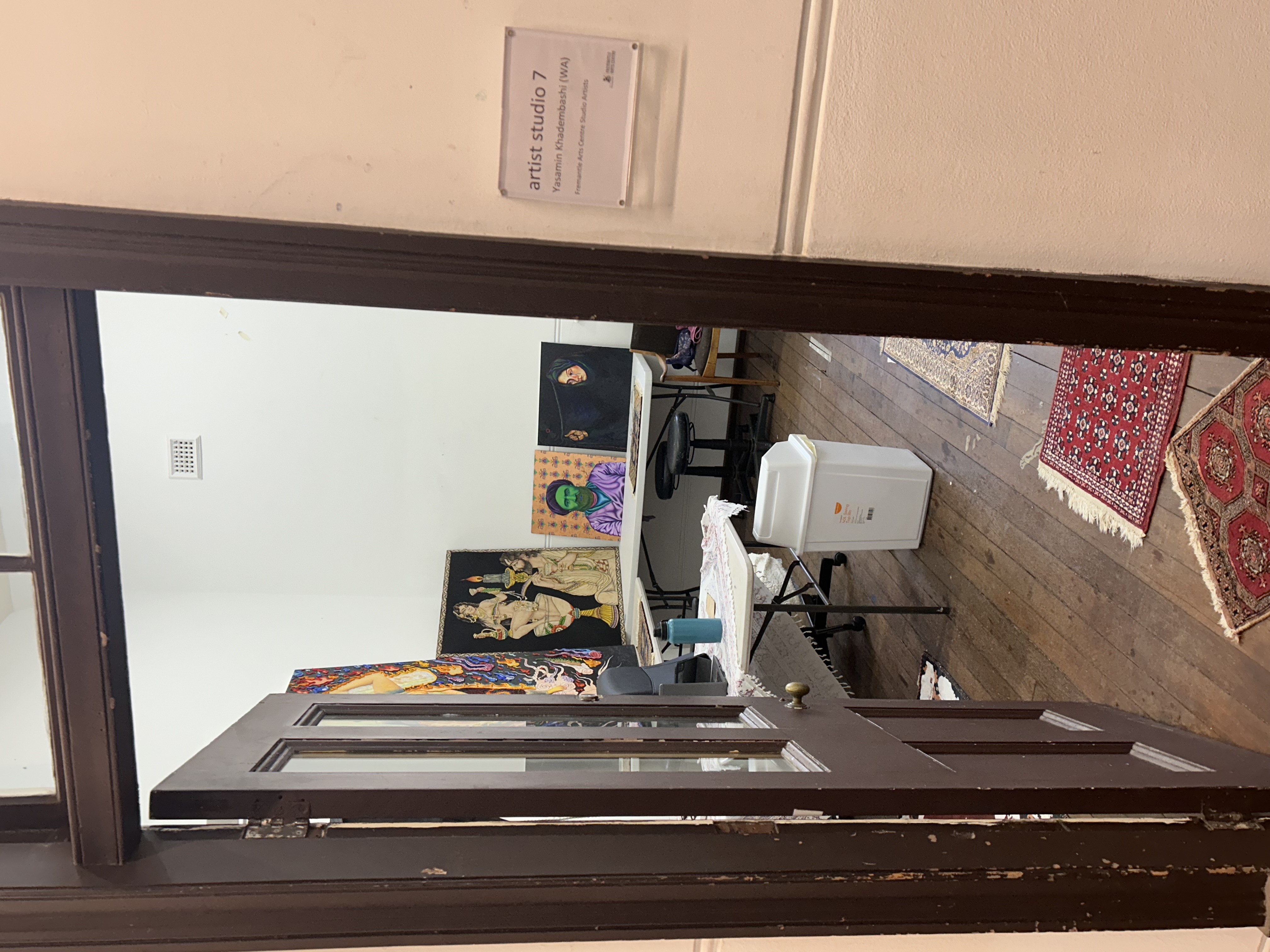

Creating a Studio That Feels Like Home From mid-January until the end of the month, I gradually moved into my new space, filling my car with boxes each week—brushes, paints, piping nozzles, pastels, charcoal, fabrics, threads, synthetic eyelashes, and my treasure trove of rhinestones and synthetic pearls. Laying out my Persian carpets on the floors, arranging my works around me, and organising my tools into drawers and shelves, I felt a deep sense of belonging. The PSAS building itself is a work of art, a historic warehouse in Walyalup’s West End precinct, standing since 1907. My studio is one of 36 within this vast creative hub, surrounded by an incredible community of artists and practitioners. Walking into this space each day, I feel both immense gratitude and an overwhelming sense of purpose. I am truly so grateful and thankful to have this opportunity to be part of such a diverse group of talented individuals within this community at PS Art Space.

Having a dedicated studio separate from home has been revolutionary for my practice. While working from my small home studio had its conveniences, it was also full of distractions—domestic responsibilities were always within reach, making it difficult to fully immerse myself in my

work. Now, in this spacious environment, I can work intensively and iteratively, developing conceptually complex, multi-layered, multi-material artworks without interruption.

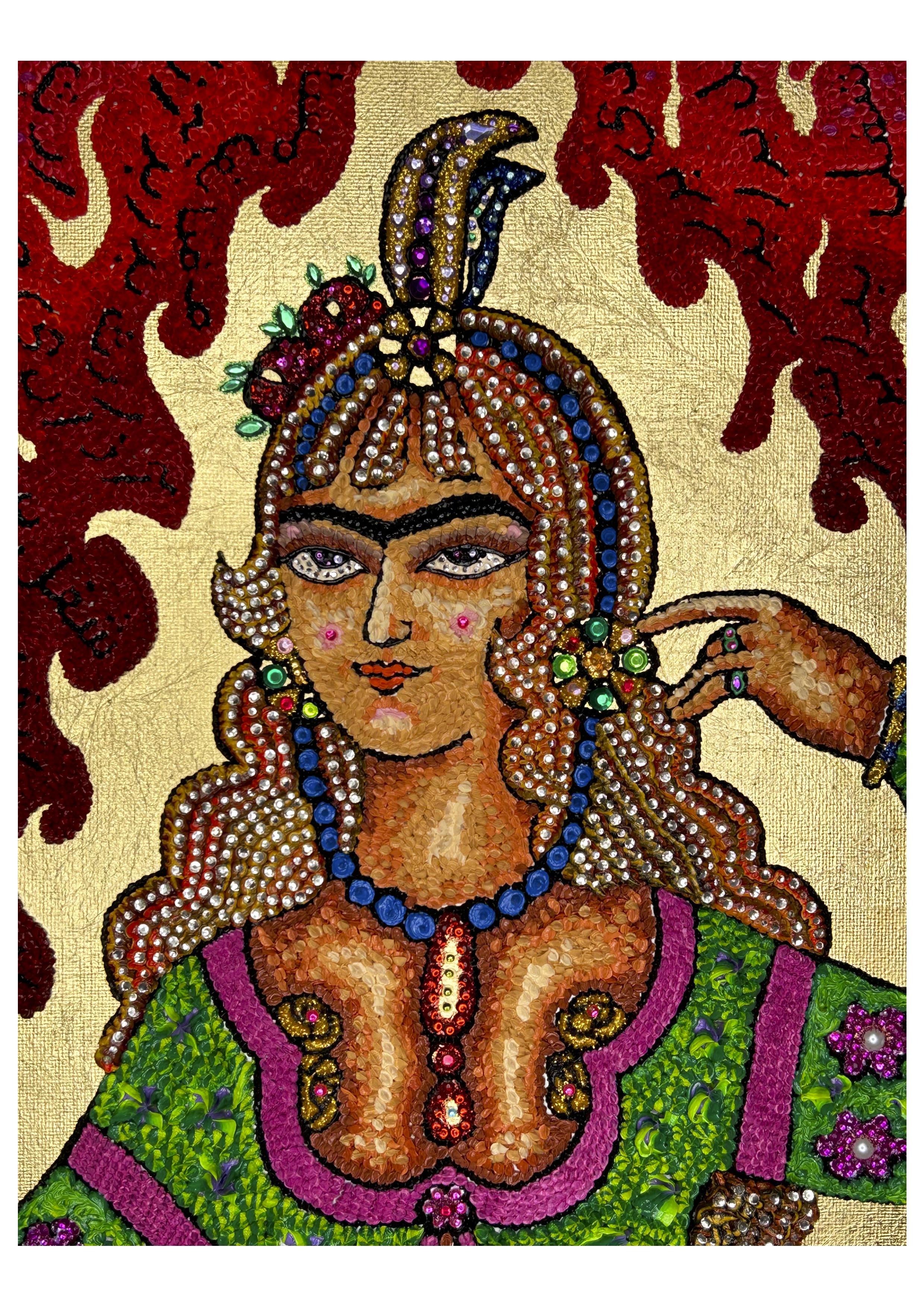

Experimenting with New Methods & Techniques I have spent hours and hours in this space refining my artistic process, expanding my approach through experimental techniques. My current project pairs impasto oil painting piped using cake decorating equipment to create richly textured, dimensional surfaces with traditional Persian miniature painting techniques and classical Western European portraiture.

The resulting paintings are tactile and visually striking, blurring the boundaries between painting and sculpture. They embody the queer, the camp, the feminine, the masculine, the grotesque, the beautiful, the powerful, the big, and the vulnerable—a celebration of identities that resist erasure.

This project aims to disrupt Western beauty ideals by celebrating diverse hairier bigger body types, darker features, and other uniquely defining characteristics within the SWANA diaspora. These proposed works aim toconfront and challenge pervasive and ubiquitous cultural narratives by personalising the political. Engaging with the community in Walyalup through this residency, enables me to humanise the identities and people depicted in the artworks, creating a deeper understanding and representation of queer individuals living and existing within Iran, the Middle East and the diaspora.

February 2025

Community & Collaboration: Second Generation

CollectiveFebruary marked my first major collaboration with the Second Generation Collective on their upcoming project, Valley of Love (Vádye Eshghe) at PICA. This project explores themes of poetic epics, culture, identity, spiritual giants, and love. I was honoured to be invited to participate in their creative workshops.

Meeting and working alongside other Iranian artists—many of whom share experiences of displacement and diaspora—has been an incredibly affirming experience. Growing up in Perth during the late ‘90s and early 2000s, I rarely encountered other Iranian people. My parents had migrated to one of the most geographically distant places from Iran, and in many ways, we were learning this unfamiliar terrain together, untethered from our ancestral lands, our family, our language, and our identity and culture. Now, as an adult, being surrounded by fellow Iranian artists feels like a breath of fresh air. The ability to speak Farsi freely, without code-switching or explanation, is something I rarely experienced during my childhood, adolescence, or even early adulthood. This sense of unfiltered connection and cultural understanding reinforces why representation is so vital—not just within the art world, but within broader socio-political contexts.

Art as Resistance & Responsibility

The importance of visibility and representation for Middle Eastern and SWANA communities has never felt more urgent. We are living through a time of brutal occupation, genocide, and systemic erasure. The settler-colonial state of Israel continues its occupation and genocidal campaign against Palestinian people. The gender apartheid in Iran and Afghanistan, enforced by the Islamic Republic and the Taliban, threatens the fundamental rights of women, queer folk and other minorities. The looming dangers of another Trump presidency pose further risks to marginalised communities globally. Here in Australia, the shameful and

cowardly decision by Creative Australia to revoke artist Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino from representing Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale reflects the increasing silencing of artists and creatives around the globe. In the face of these ongoing atrocities, art is not just expression—it is protest, resistance, and a demand for justice. This moment in history calls for artists to be unapologetically bold, to disrupt, advocate, document, and

create work that challenges systems of oppression.

Looking Forward: Expansion & Exploration

As I settle into this residency, my focus remains on pushing the boundaries of my practice, refining my techniques, and amplifying the narratives that

have long been silenced. This studio is not just a place to work—it is a haven for experimentation, play, and expansion. Over the coming months, I aim to bridge the personal and political, further embedding my works within queer feminist research, bodily autonomy, and de-colonial resistance. Through these paintings, I hope to humanise,represent, and reclaim identities often denied visibility—queer people, SWANA communities, and those resisting oppression. For now, all I want to do in this space is: Create. Make. Explore. Experiment. Play. And push the limits of what my practice—and art itself—can be.

March 2025

Controlled Chaos: A Method of Resistance

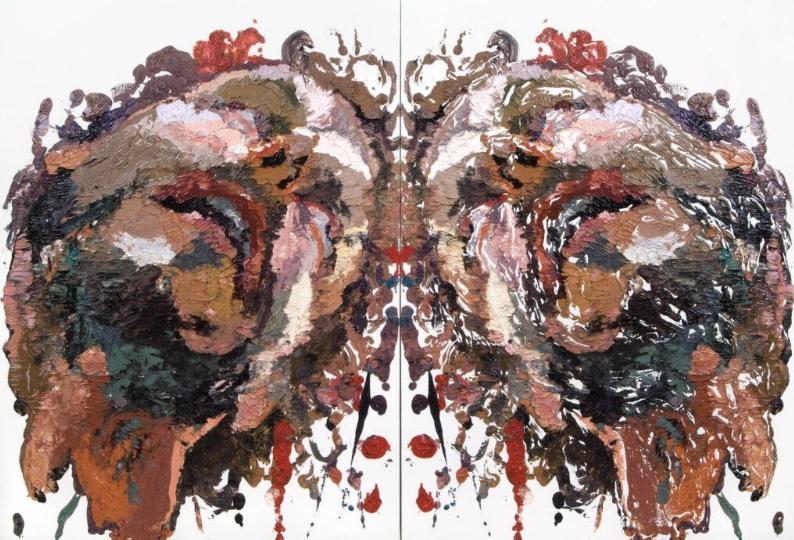

March signified the first time during the residency where I was able to fully focus on research and experimentation, honing in on a specific method and medium I initially began exploring during my previous residency at MJAC. This technique entered my practice quite organically, rooted in a memory of watching a short film or documentary years ago on the artist Ben Quilty. In it, Quilty worked with impasto oil paint, building thick, luscious layers to create expressive and visceral portraits. The most magicalmoment for me was when he completed a work, then picked up another canvas of the same size and pressed it directly onto the finished painting. This act left behind a mirrored impression—an echo of the original.

This gesture of both duplication and destruction profoundly impacted me. It reminded me of the simple inkblot tests we used to do as children: choosing our favourite colours, placing them at the centre of a page, folding it in half, and unfolding a completely new mirrored image—familiar, yet entirely transformed. There was something deeply nostalgic and instinctual in this act. But what resonated even more was its metaphorical weight. The act of altering or even ‘destroying’ what is perceived as beautiful or precious became a powerful visual metaphor that closely aligns with the conceptual frameworks of this project. My practice often interrogates the construction—and deconstruction—of identity, particularly through the lens of gender, queerness, displacement, and diasporic experience within SWANA and Muslim communities. In this context, the method took on new meaning.

To create something whole, only to distort, flatten, or fragment it, mirrors the lived experiences of women, queer, and trans folk—those who areconstantly navigating systemic violence, silencing, and social erasure. The imprint left behind on the second canvas becomes symbolic of how we’re shaped by external forces: culture, religion, patriarchy, white supremacy, heteronormativity. These forces press against us until we’re no longer sure which version of ourselves is the ‘original and which is the impression. The ephemeral and transformative nature of the process is what drew me in most. It evokes the fragility of memory, the instability of identity, and the tension between visibility and disappearance. The original image is never preserved in its entirety—yet it is not entirely lost either. What remains is a trace, a ghost, a new form that carries with it all the weight of what came before. It’s a process of loss, but also one of resilience and regeneration.

By surrendering to the unpredictability of this technique, I am relinquishing control—mirroring the lack of control many of us experience in our bodies, in the narratives told about us, or in the places we are allowed to exist freely. The method became not only a medium of making, but a conceptual strategy that deepened my understanding of this project’s themes and allowed the work to evolve in ways that felt urgent, intuitive, and deeply personal.

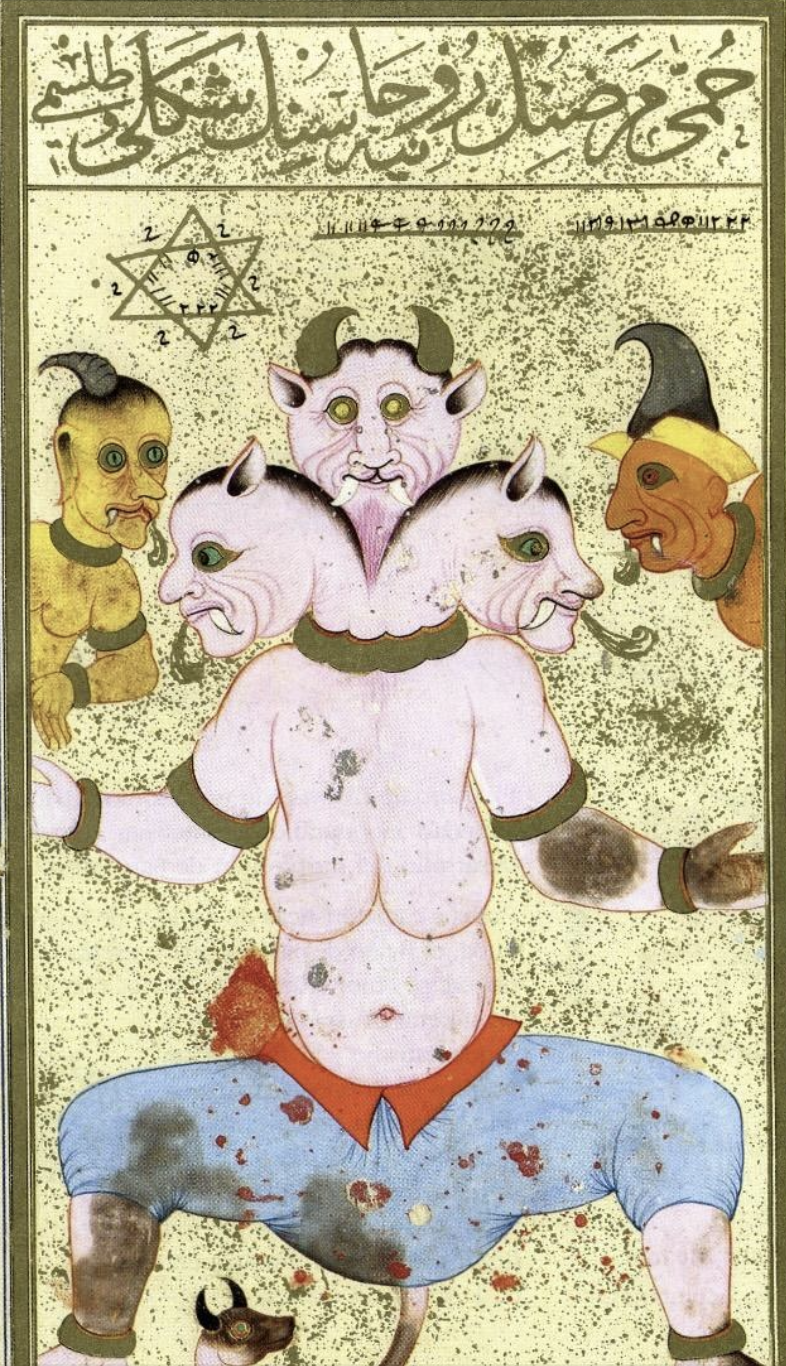

This month, I leaned more fully into the material and conceptual possibilities of my Rorschach painting method—testing its limits, its failures, and its potential for transformation. Building on my initial explorations, I turned to one of the most enduring mythological figures in Iranian and Islamic history: the Jinn. The Jinn, often seen as a demon, spirit, or trickster, became a vessel through which I could continue pushing the boundaries of figuration, abstraction, and storytelling within my practice. My fascination with Jinn dates back to 2022, when I created my first impasto painting of one. That work inadvertently sparked my obsession with the physicality of impasto oil paint—its density, its tactility, its resistance. One of my art heroes who is known for his Jinn’s, is renowned artist Khadim Ali, who has deeply explored and reimagined the subjectivity of the Jinn in his work. From sprawling murals to delicate watercolours and intricately woven tapestries, Ali’s art draws from Persian miniature painting, Islamic mythology, and calligraphy to reclaim the Jinn as a symbol of resistance, exile, and duality. His practice has been foundational in shaping how I engage with myth as both metaphor and medium.

With this third Jinn painting, my intention was to test my current Rorschach-inspired technique more rigorously and resolve an ongoing issue: the transference of the painted image onto the second canvas. Initially, I assumed the problem lay in the angle or pressure of the pressing process. But after repeated trials, I discovered that the inconsistency stemmed from the drying time of different pigments—especially the piped acrylic mediums I use. Some areas were drying too quickly, forming a thin film that prevented a clean transfer. I learned that to achieve the best results, the entire image needs to be piped within one to two days. Any longer, and the paint loses its ability to adhere properly, compromising detail and clarity.This discovery presents a new challenge, especially when working on large-scale canvases (up to two metres), where intricate Persian-inspired designs depend on fine detail and decorative density. I wouldn’t call the outcome of this painting a success in terms of final image resolution—but it wasn’t a failure either. It provided essential insight into how this method functions under pressure, and how the materials respond to time, touch, and surface. Another unexpected issue arose from the paint’s volume: when two fully piped canvases are pressed together, the unevenness and density create a kind of suction. This prevents the paint from sticking evenly, making the transfer irregular. Going forward, I plan to leave the background flat and focus the piped paint on the subject only. I’ll also work to smooth the surface more deliberately to prevent air from getting trapped between the layers. Wish me luck!

April 2025

The Divine, The Monstrous, and The Human

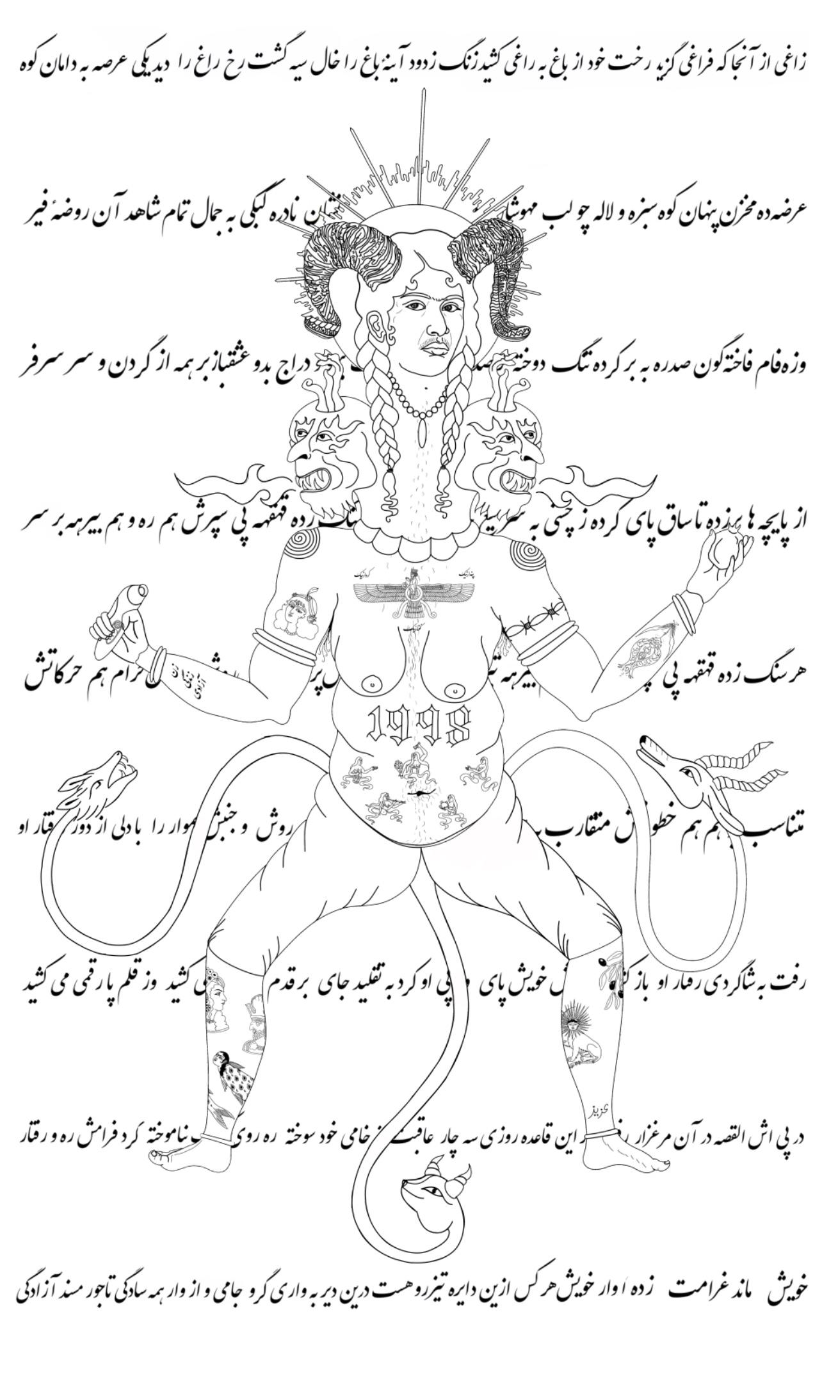

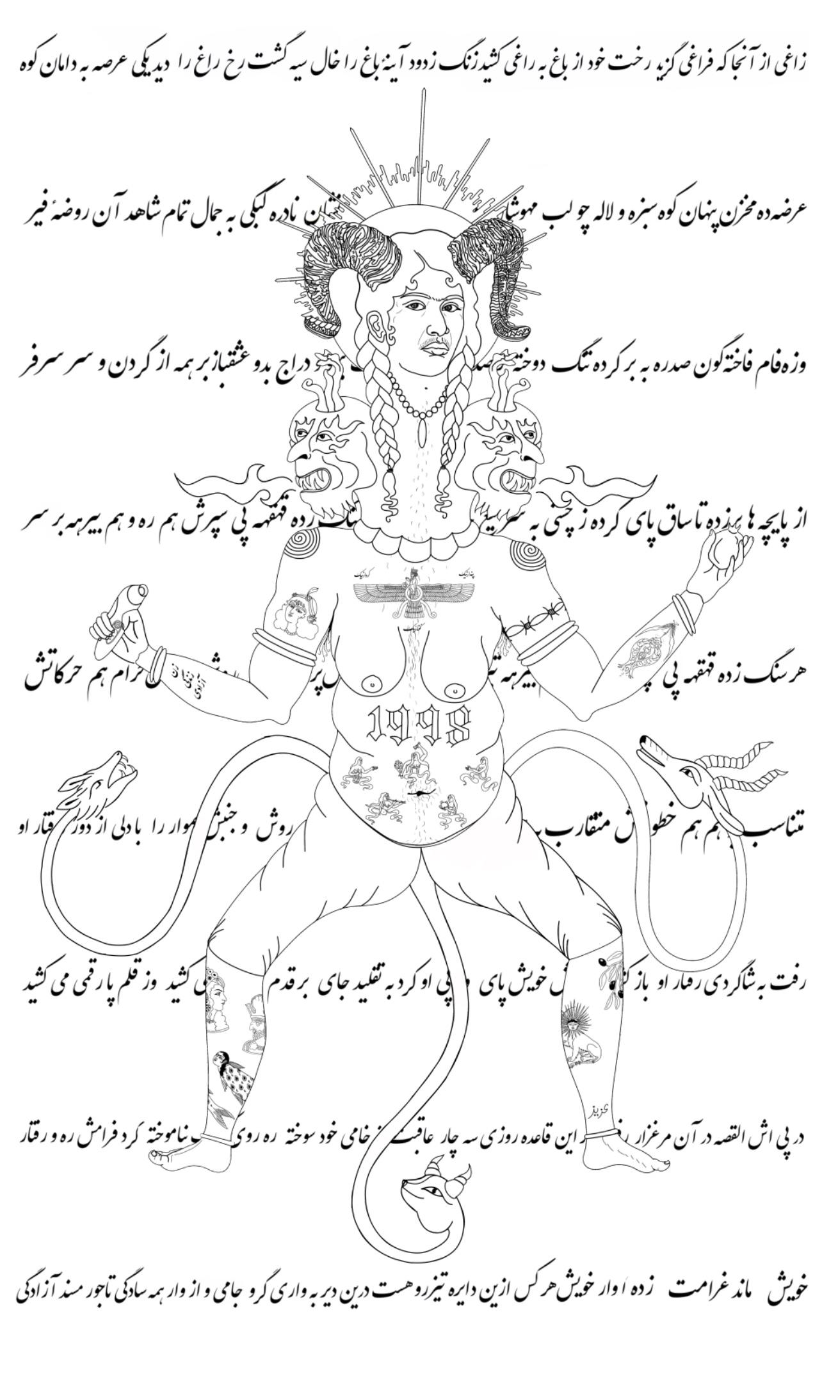

By April, I began developing the design for one of three major paintings I plan to complete during this residency. This work continues my ongoing exploration of mythology through a distinctly queer and feminist lens, drawing deeply from Persian and Islamic iconography while radically reinterpreting it. Inspired by an Ottoman manuscript illustration of the three-headed Jinn Huma by Mehmed ibn al-Hassan Emir Suûdî, the figure I’ve envisioned embraces multiplicity—embodying both the divine and the monstrous, the mythical and the real.

At the heart of the composition is a purposeful fusion: two Jinn heads are directly connected to a central human figure, collapsing the boundary between imagined and lived experience. The divine, feared, or monstrous becomes tangible, intimate, and embodied. Here, the Jinn is not just a folkloric spectre, but a vessel for rage, defiance, and sacred transformation.

Their presence challenges the viewer’s gaze and reclaims space for marginalised bodies—particularly those of queer women and gender non-conforming people who navigate both visibility and surveillance. The figure itself is bold, tattooed, and intentionally excessive. The tattoos function as a living archive—markings of identity, memory, and survival. From the ancient Zoroastrian Faravahar to the defiant “1998” sprawled across the belly, every symbol carries personal and cultural weight. In Iranian and Islamic contexts, tattoos are often taboo—seen as transgressive or impure. Here, they become declarations of autonomy. The body is not modest, but sacred and unruly—resisting erasure and celebrating its right to be adorned, decorated, and seen.

Surrounding this central figure is a precise arrangement of Persian calligraphy, drawn from the fable The Crow and the Partridge—a moral tale that warns against changing oneself to appease others. The text lines the figure in even, rhythmic rows like a protective aura, echoing illuminated manuscript traditions where language and image coalesce. But here, the script is not just decorative—it’s spellwork, boundary, and barrier. Illegible to some, it becomes a quiet act of refusal; legible to others, it offers connection, intimacy, and shared knowledge. Formally, I sought to mirror the balance of classical manuscript design while infusing it with subversive energy. The figure’s pose is symmetrical yet volatile, her limbs sprouting animal-headed tails that gesture to chaos and transformation. I first hand-sketched the composition, working intuitively on paper before transferring it into Procreate, where I refined the detailing and structure. The digital process allowed for precision and intricacy, echoing the ornamental logic of Persian design. Every element—gesture, symbol, pattern—was chosen with care to disrupt, reclaim, and expand.

This painting is about more than just visibility—it’s about rewriting visual language and reclaiming space within traditions that historically excluded us. The grotesque becomes sacred. The Jinn, once feared, becomes our mirror. And the figure at the centre—inked, enraged, mythic—takes up space where saints and warriors once stood.

May 2025

This month has been an absolute whirlwind—probably the busiest I’ve ever been—but it’s also felt like a dream come true. May marked the beginning of my second residency at Fremantle Arts Centre, and funnily enough, I was placed in Studio 7 at both PSAS and FAC—clearly, now its my lucky number.

Alongside kicking off the FAC residency, I also completed one of the most intense projects I’ve ever worked on: my grant application for funding my solo exhibition. This process was brutal. The amount of research, editing, budgeting, and hoop-jumping involved was low-key insane—and all for something that statistically isn’t likely to get funded (the success rate sits at 18%). It’s deflating to put in that level of work—to tick every box, justify every dollar, and finesse every sentence—knowing there’s a good chance it still won’t be approved.

It’s moments like these where the grind can feel almost pointless, where the burnout feels bone-deep. Working without consistent funding or even a livable wage in this industry can be deflating. But still, I wouldn’t trade what I’ve built. I remind myself that we’re all on different paths, and that it’s okay if mine looks different. Something I don’t often talk about is the fact that I’ve been a carer since I was 10. Out of respect for my family’s privacy, I won’t go into details, but this has been a fundamental part of my life and something that deeply shapes my perspective. It’s taught me patience, kindness, and to never assume anything about someone’s journey. You never really know what people are carrying.

Balancing multiple projects, two residencies, paid work, and family responsibilities can feel like a Herculean task. But I don’t take it for granted. My responsibilities as an artist and as a family member are equally central to who I am. My unwavering love and loyalty to my family are rooted in my Iranian heritage, where kinship is everything. Our family dynamic may be unconventional, but it is radical in its love, generosity, and mutual care. So, if you ever catch yourself spiralling in self-comparison, I hope you give yourself some grace. Everyone’s carrying something. Keep grinding—your time will come.

I’m profoundly aware of how rare and precious it is to be openly queer within a Middle Eastern household. In many cases, being visibly queer in a SWANA (South West Asian and North African) or diasporic context can result in rejection, isolation, or even violence. The fact that I’m able to live authentically, be embraced by my family, and pursue an artistic practice rooted in queer identity is something I never take for granted. I hold that privilege with deep respect and tenderness—because I know that for many in my community, it’s not a reality. That awareness fuels my practice, and it’s part of why I’m so committed to creating work that makes space for those who can’t yet safely take up space themselves.

Now, back to the chaos that is the studio. Dividing my work between PSAS and FAC has been the best thing for my brain. It helps me manage the sheer scale of what needs to be done. Some works are nearly finished, some are mid-process, and some are still sitting in sketchbooks as vague ideas. I don’t recommend doing two residencies at once (ever), but weirdly, it’s helped me compartmentalise. I’ve dedicated the FAC studio to my paint-piped, carpet-inspired works, while PSAS is reserved for my large portrait paintings. My hope is that by keeping these spaces distinct, I’ll manage to complete everything in time.

May has also brought with it a whole new layer of anxiety. Don’t get me wrong—I’m incredibly grateful for these opportunities—but with them comes the pressure to deliver. Most of it is self-imposed. The perfectionist in me always wants to tweak, finesse, adjust. The work is never “done.” I’m constantly worrying about archival quality—Will the metal leaf tarnish? Will the rhinestones fall off? Will the synthetic hair or pearls disintegrate over time? When your work relies on unconventional materials, experimentation becomes high-stakes. You want spontaneity, but you also want control. You want permanence in the ephemeral. It’s a complicated place to sit in.

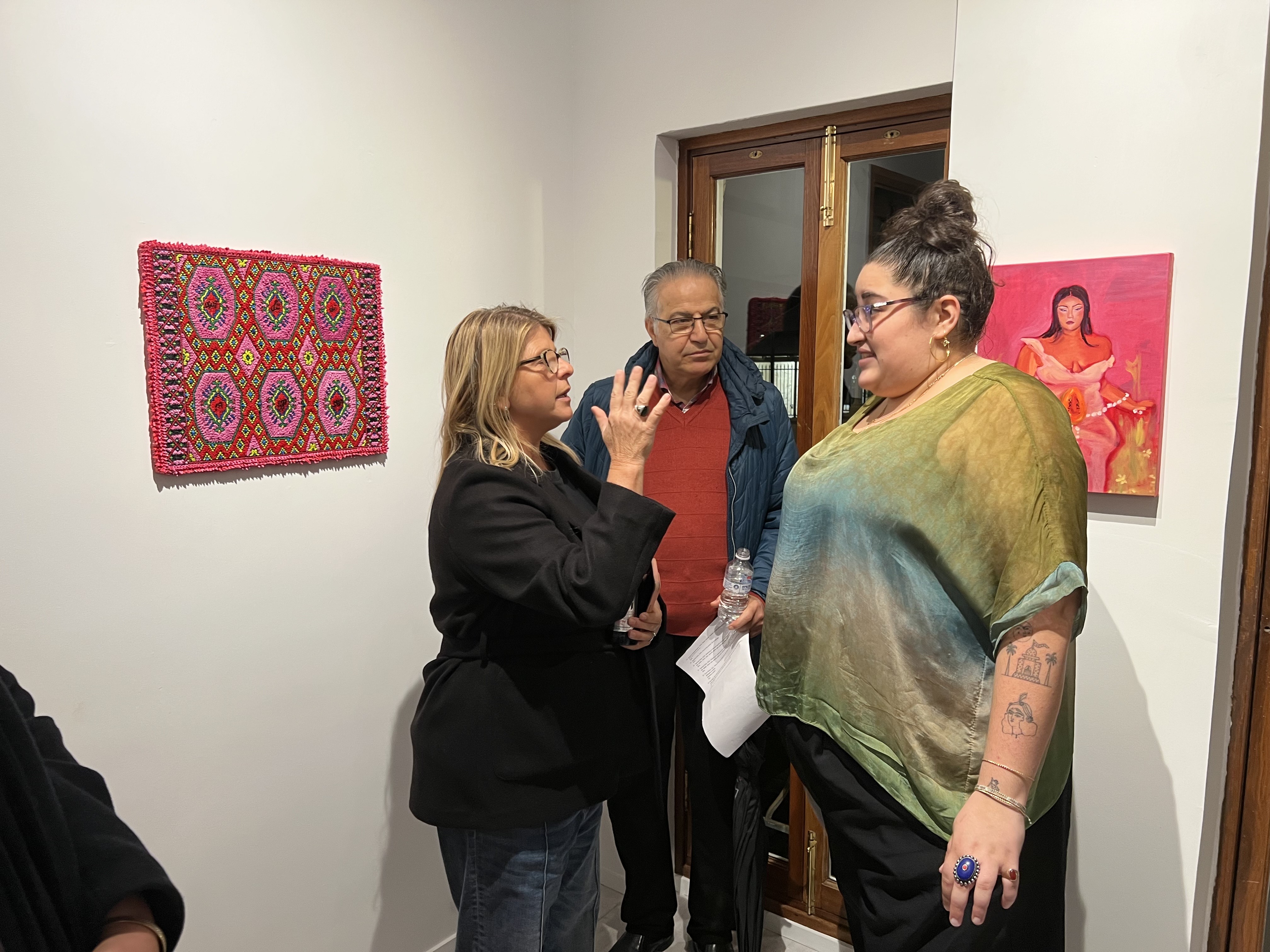

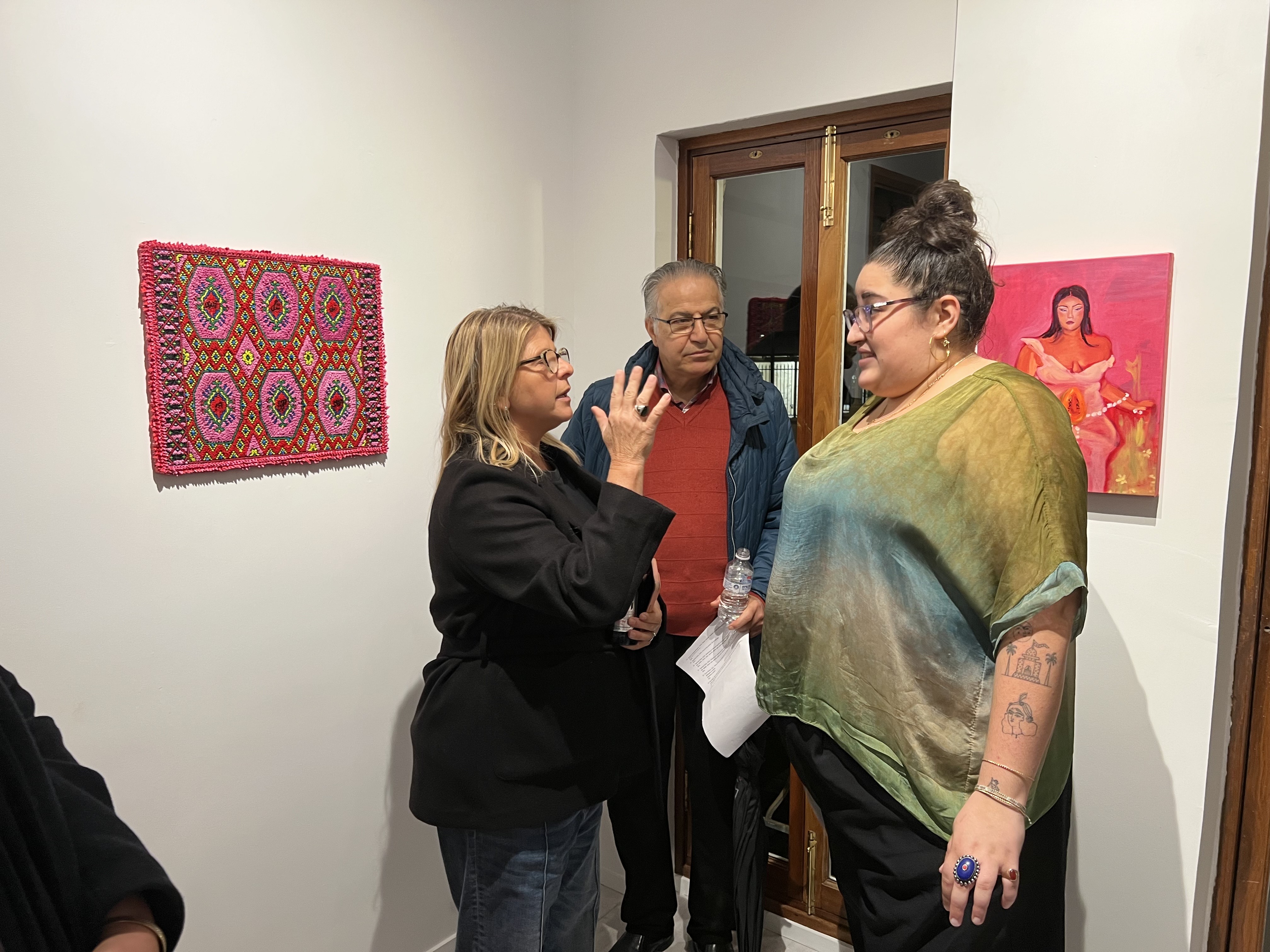

One of the most monumental experiences this month was the opening of In Spite (of), a group exhibition curated by Dr Lydia Trethwey at Nyisztor Studio. The show featured an incredibly talented lineup of artists: Emily Palmer, Bethan Power, Nina Raper, Leila Simpson, and Yasmine Soto. Lydia’s curatorial essay put words to many of the emotional and political undercurrents running through the works. She wrote, “Queer joy is not inspirational porn; critique of Islamophobia is not consumable. And yet, the viewer can easily choose to consume marginalised experiences. Many of the artworks in this show navigate such tensions, simultaneously inviting the viewer in, and pushing them out.” The exhibition sat with those contradictions and held space for both beauty and discomfort.

The opening night, on the 24th of May, was one of the most validating moments of my career so far. I had no idea what to expect and was genuinely nervous—but the turnout blew me away. Being surrounded by friends and family, many of whom have been with me since I was a kid dreaming of being an artist, was incredibly emotional. They’ve seen the whole arc—from the first scribbles to now—and have never wavered in their support.

I’m quite introverted by nature, so speaking with so many people that night was overwhelming in the best way. The curiosity and generosity people brought to the works—asking questions, engaging deeply—was the highlight of the night. Thank you to everyone who came, supported, and shared that moment. It meant more than you know.

Working between two studios in Fremantle—PSAS and FAC—has helped me build strong relationships with local artists, curators, and institutions. It’s opened up new conversations, new possibilities. And even though it’s exhausting, it’s also exactly where I want to be. So here’s to the exhaustion, the joy, the fear, and the hustle. We move.